26: Playing Cards: Rarity, Value, Dating, Sellers and eBay

Notions like rarity and monetary value are slippery customers and need careful handling. And there are still plenty of misleading descriptions on eBay - as well as looney prices!

Unlike stamps, bank notes and possibly cigarette cards, there is very little known about the size of print runs of most packs of cards. The Waddington archive contains some information about some of their production, and there is information about tax revenue from playing cards even back in the 19th century, but most of the printing records have long disappeared. This lack of reliable records means that no-one is in a position to produce the equivalent of the Stanley Gibbons stamp catalogues for cards. Just as well, I say, or the dealers would be trying to manipulate the market more than they do now.

Rare is not a term to be used lightly and, in fact, it's probably better not to use it at all. Fairly uncommon, unusual and similar terms are preferable in that they make no claims as to how many such items there might be in the world. Indeed, some of the sellers on eBay, in particular, make ludicrous claims about rarity. From what has appeared on eBay during the past two or three years it's possible to deduce that even some mid to late 19th century packs are pretty common. I would want to know on what basis the claims of rarity are made. One of the most obvious metrics is how often one has seen the pack in question. But who is to say whose experience of observing playing cards is better or more valid than someone else's? Length of time might be one criterion. My own gauge of rarity relates partly to what I know of the existing information about production and tax revenue and how often I've seen a particular pack; in my case this experience of seeing cards goes back to about 1945, so a span of some 70 years observing and admiring cards (not necessarily owning them). Useful though this is for me, I can't expect others to rely on my say-so or even believe me, so it all boils down to an individual's assessment of a pack, which (including my own) may sometimes be incorrect.

BY THE WAY the erect feather AS by Goodall is NOT RARE; the recent claims on eBay are wrong and misleading. Who invented that fairy story? When I pointed out its relatively common occurrence to one eBay seller, this is the response I got. I reproduce it here as it appeared (including punctuation and spelling mistakes).

"To clarify my statement. The Ace with the raised feather was only produced for 3 yrs 1862/5 during that period Goodall were manufacturing approx 330,000 decks per yr, so a total of approx 1 million decks in total. The common Ace of spades was introduced in 1865 and ran untill 1945 under the de la Rue manf from 1922. Production figures for that period are approx 300 Million therefore the raised feather version was only produced on 1% of all the decks produced giving the age of the raised feather version, I would say its rare compared with later version. This info was given to me by my partner who is an avid collector of Goodall cards, over 1200 decks in his collection, and for your info he as approx 50 decks of raised feather.

Hope this is helpfull."

This is not the way to work out (relative) rarity, even if the information is accurate, which it isn't. You have to compare like with like. In this case it means comparing the number of erect feather aces with the roughly contemporaneous ones, in particular the one that became the normal one, with a lower feather. But such aces have to have square corners and no indices to be remotely comparable. Dragging in figures (from where?) up to the 1940s makes no sense at all; it would be just as helpful to compare erect feather aces with the number of baked beans Heinz made during the 20th century! I would have thought having 50 examples of the item under consideration was a bit of a give-away! The dating issue is taken up again in more detail on page 41.

And where does value come into all this? Well, real value in my view is the position a pack holds in the history and development of cards right up to the present day, in other words its relevance to other packs of a similar type. Monetary value, on the other hand, is a personal opinion. Every collector should be an expert on what he or she is prepared to pay for a particular pack. But there is no such thing as an absolute value (for anything, not just playing cards). And collecting as an 'investment' is a mug's game.

Sellers' descriptions of packs are often misleading: quite often unfounded claims (e.g. of rarity) are made, and the descriptions are embroidered to make the cards sound more desirable than they are. The best presentations on eBay are those which modestly make no claims and, in particular, those that give good illustrations of what's on offer. The potential buyer can then usually see clearly for him/herself. This isn't foolproof, as scans/photos don't necessarily show up delamination and separation due to damp, for example. Incidentally, as far as the UK is concerned, items on offer on eBay (and elsewhere) are subject to the Trade Descriptions Act, so it is incumbent upon the seller to give accurate information, even if it's minimal. There are, sadly, eBay sellers who won't listen to information which challenges their descriptions; their listings are full of factual misrepresentations.

My concern in all this is a desire to impart knowledge, something I have spent my life doing. (How well, others have to judge.) If someone knows a description of a pack of cards is inaccurate, then there is no problem, but I'm concerned about those who do not have the knowledge to make a proper assessment. It is unsafe to rely solely on the descriptions of sellers. (Do I notice a parallel here with the Brexit campaign?!)

The prices being asked at the moment (2018) are in many cases ludicrous, whether fixed price or in auctions. Common-or-garden packs have unrealistic price tags put on them. Dealers seem to think that collectors are simply greedy and will get excited if they see items in their collection go up and up in price. That assumes that the cards actually sell, of course. If I buy a pack for $300 one year and then the next year a similar one is on offer at $1,200, I'm afraid I don't get ecstatic with a lust for the money I seem to have made. Again the question is, does the pack actually sell for the asking price? Even if it does, what happens next time one comes on the market? I'm just a very difficult customer and intend to remain so! I hope there are many more like me!

Tax records and similar sources of production levels

Although there are not enough extant examples of card production levels, there are some sources which give sporadic, but important glimpses of the relative size of different makers. (Some of this information is also given on page 30.) We have production figures for each maker from the year 1824. I give them below in the format: MAKER: Home: Export figures (number of packs). These figures presumably include any of the few non-standard packs produced at the time.

BROTHERTON: 2,334: 5,352

CRESWICK: 39,160: 16,844

FULLER: 144: none

GOODALL: 3,497: 756

HALL & BANCKS: 37,500: 31,410

HARDY: 17,540: 32,736

HUNT & SONS: 97,000*: 20,684

REYNOLDS & SONS: 2,056: 1,464

STONE**

STOPFORTH: 4,446: 3,860

WHEELER, H: 1,560: 1,893

WHEELER, W: 1,760: 600

*There is an error (uncorrected misprint?) in the table of figures from which these data are taken in respect of Hunt. The total sum of tax paid is given as £13,625, which is equivalent to 109,000 packs; the lower figure gives a tax total of £12,125. I don't know where the misprint is, but we can say that their output (the biggest of all the makers) is between these two figures.

**Stone does not figure in this particular list, so seems to have produced no packs in 1824, but he is mentioned in the export list as having over 11,000 tax-exempt aces in hand, of which 6,000 were returned to the Tax Office and the rest were reassigned to Creswick. I assume from this that Stone's firm was coming to an end around this time.

We also have a snapshot of one month's domestic production, January, 1825, which also shows the slightly different ways of working as between the makers. The figures refer to packs.

BROTHERTON: 240

CRESWICK: 3,840

FULLER: None

GOODALL: 350

HALL & BANCKS produced no packs, but ordered and received 7,100 new aces.

HARDY produced no packs, but ordered and received 7,600 new aces.

HUNT & SONS: 8,000

REYNOLDS: None

STONE, despite his apparent demise, ordered and received 578 aces.

STOPFORTH: 600

WHEELER, H: None

WHEELER, W: 240

Presumably, most makers had their stock of aces in hand by the end of the year (1824), but Hall & Bancks and Hardy restocked in the first month of the next year. Note the vast range of production in 1824 from only 144 packs by Fuller to the 97,000 pack by Hunt. It's not surprising, therefore, that Hunt packs are so common today, with Creswick, Hall (& Bancks) and Hardy featuring strongly, too. On the other hand, the mighty Goodall and Reynolds were still minor players at this time.

Later, in the 1850s, De La Rue kept a note of the year-on-year card production of its own and of its competitors. Several of the earlier makers have disappeared and others have increased in size, especially Goodall and Reynolds. These are the figures.

MAKER/Date: Home : Export

BANCKS 1855: 42,200 (17.7%) : 7,795 (3.1%) (successors to HALL & HUNT)

1856: 41,500 (14.1%) : 6,000 (1.7%)

1857: 37,200 (13.4%) : 2,832 (0.5%)

1858: 33,600 (11.3%) : 3,792 (1.0%)

1859: 33,100 (10.6%) : 2,400 (0.6%)

1860: 28,700 (9.7%) : No figure given

DE LA RUE 1855: 69,400 (29.2%) : 54,966 (21.9%)

1856: 93,060 (31.7%) : 90,662 (26.1%)

1857: 93,000 (33.6%) : 183,392 (38.8%)

1858: 108,150 (36.3%) : 122,718 (32.4%)

1859: 120,700 (38.5%) : 131,634 (33.3%)

1860: 117,300 (39.9%) : 110,584 (36.0%)

GOODALL 1855: 47,736 (20.1%) : 36,178 (14.4%)

1856: 50,500 (17.2%) : 78,036 (22.4%)

1857: 55,000 (19.9%) : 82,950 (17.6%)

1858: 58,800 (19.8%) : 48,226 (12.7%)

1859: 65,450 (20.9%) : 49,603 (12.5%)

1860: 68,000 (23.1%) : 34,398 (11.2%)

REYNOLDS 1855: 60,901 (25.6%) : 90,372 (36.0%)

1856: 72,860 (24.8%) : 121,968 (35.1%)

1857: 71,261 (25.7%) : 175,604 (37.2%)

1858: 68,020 (22.9%) : 178,958 (47.2%)

1859: 70,882 (22.6%) : 196,374 (49.7%)

1860: 64,576 (22.0%) : 152,928 (49.8%)

The other four makers in the list are small by comparison, though Whitaker has a reasonable, but erratic output.

STEER 1855: None : None

1856: 2,600 (0.8%) : 4,056 (1.2%)

1857: 3,500 (1.2%) : 17,592 (3.7%)

1858: 2,900 (0.9%) : 5,640 (1.4%)

1859: 2,376 (0.7%) : 3,840 (0.9%)

1860: 1,200 (0.4%) : 144 (0.04%)

The 1857 figures are out of line and why there is such an increase in export is unclear. From the extant examples of his packs it is reasonable to assume that he didn't make the cards in England, but imported them from Turnhout.

WHITAKER 1855: 4,300 (1.8%) : 42,660 (17%)

1856: 23,790 (8.1%) : 35,330 (10.1%)

1857: 6,600 (2.3%) : 3,636 (0.7%)

1858: 18,350 (6.1%) : 19,603 (5.1%)

1859: 13,100 (4.1%) : 10,956 (2.7%)

1860: 7,600 (2.5%) : 8,508 (2,7%)

The figures are somewhat up and down, and his packs, too, appear to have been made in Turnhout.

Wiffin, who is also listed, is a somewhat obscure character, who eventually joined Woolley & Co: he may have imported cards like the other two, but his output was tiny and non-existent in some years.

WOOLLEY & CO. (listed as Webb, who was actually a member of the board of the firm)

1855: 9,970 (4.1%) : 696 (0.2%)

1856: 9,372 (3.1%) : 3,600 (1%)

1857: 10,300 (3.7%) : 6,456 (1.3%)

1858: 7,200 (2.4%) : None

1859: 7,350 (2.3%) : 408 (0.1%)

1860: 6,624 (2.2%) : 444 (0.1%)

Clearly a small player at this point, although the firm became more important from the late 1860s onwards.

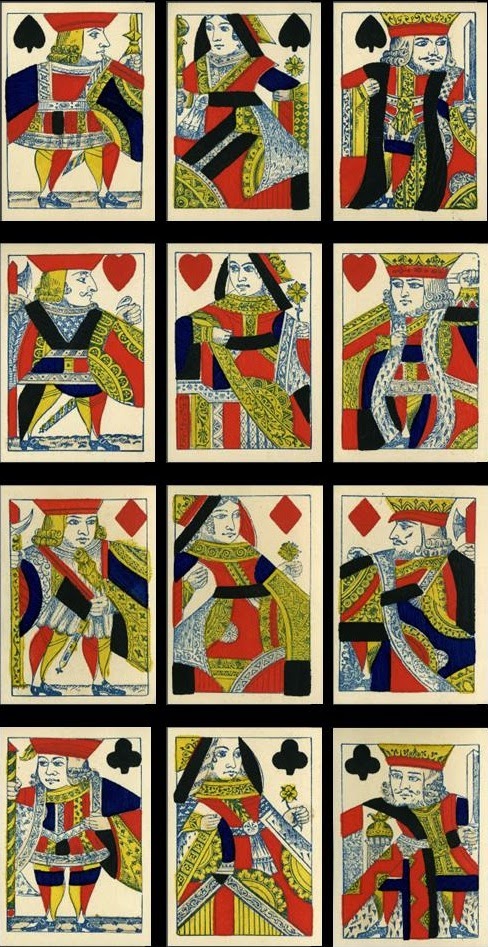

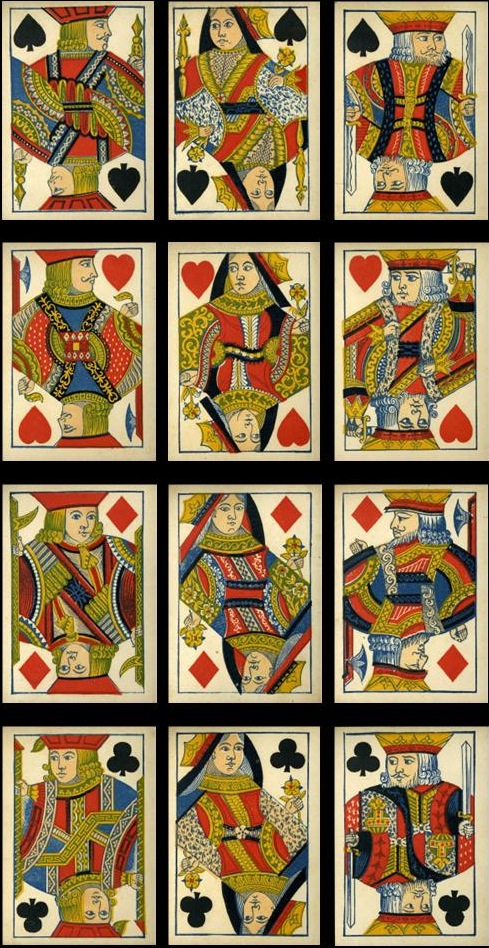

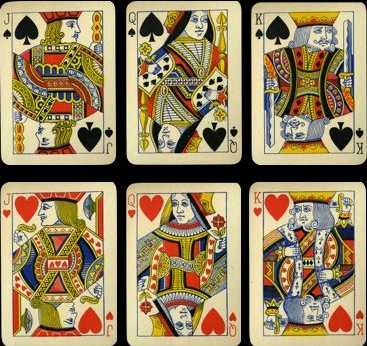

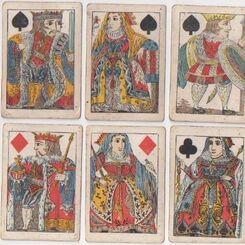

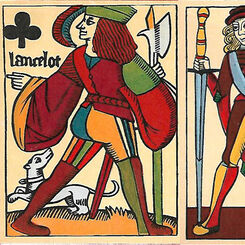

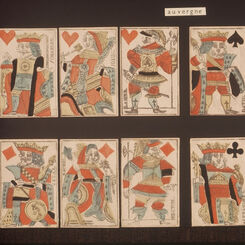

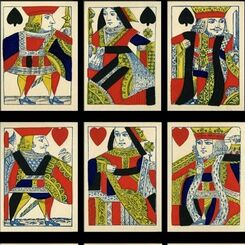

And what are the cards like that are commonplace? Here's a selection from the 19th century. The selection is based on these and other production figures that have survived. The biggest makers in the 19th century were Hunt, Hall, Creswick, and later on Goodall, De La Rue, Bancks and Reynolds. (For details, see page 30►)

Hunt/Bancks, c.1820-75

Reynolds, c.1830-85; Reynolds, c.1865-80

Reynolds, c.1830-85; Reynolds, c.1865-80 De La Rue D4.1 with Old Frizzle, 1862-67

De La Rue D4.1 with Old Frizzle, 1862-67

De La Rue, D5, c.1865-75

De La Rue, D5, c.1865-75

De La Rue, D6 (six courts turned), c.1870-1900 (later packs from the 1880s with indices)

De La Rue, D6 (six courts turned), c.1870-1900 (later packs from the 1880s with indices)

All later types (D7, D8, D9) until c.1927 are common.

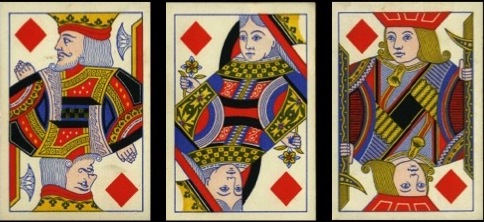

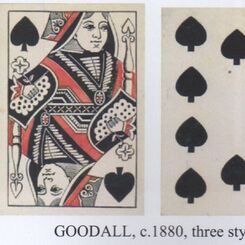

Goodall G3 (unturned), c.1860-70

Goodall G3 (unturned), c.1860-70

Goodall G4.21 (turned, cut down hats and crowns), c.1875-85

Goodall G4.21 (turned, cut down hats and crowns), c.1875-85

Goodall G6, c.1900-30

Goodall G6, c.1900-30

Plus all other later types (G4, G5, G7 (bridge width), G8) until c.1925; the last three are especially common. Of course, if you add in features other than the courts, then people might want to pay more for such packs; for example, whether the AS is Garter, Old Frizzle or a maker's ace, or if the back design has some significance.

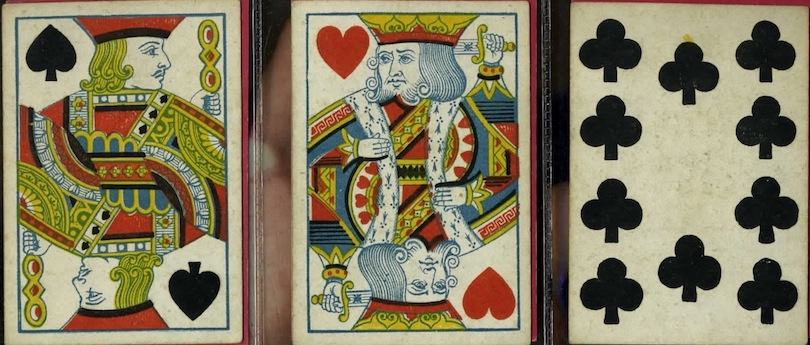

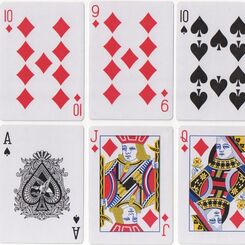

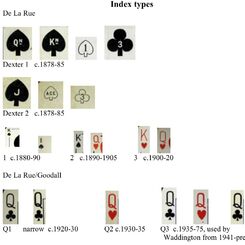

I also see a lot of wrongly dated packs on offer on eBay. Quite often I'm sure most collectors spot the errors, but those collectors who are fairly new to the game may have less information at their finger tips. For example, you often see De La Rue packs on offer which are dated as 1890s, but which are from c.1930 - a poor piece of misrepresentation. Here's one from eBay.

These were dated 1895 by the seller (very precise!), but, in fact, the AS has indices that were introduced only after De La Rue took over Goodall in 1922, so that's the earliest they could be and they could be later still.

There's a guide to dating De La Rue, Goodall and a few, later Waddington cards with Goodall courts on page 41. Here are a few further pointers.

Details of the manufacturer

There are extra indicators such as the postal district of the address given for Goodall's Camden Works. Before De La Rue's take-over (1921/2) it's NW; after the take-over it's EC1. Quite a move for a building!! The latter one is actually that of De La Rue's own Bunhill Row. And Registered Trademark appears on the Goodall AS after the take-over from c.1925 onwards. Goodall's Camden Works were sold in 1929, so any reference to it on boxes indicates a date of manufacture earlier than that.

As an example of misdating, I'll return to the message higher up the page that I was sent regarding the erect feather AS by Goodall. Note the dates given. The packs concerned were bézique packs, probably from a four-pack set. These sets were introduced by Goodall in 1868, so 1862/5 is simply wrong. So even if the calculation of rarity made sense, it falls in any case, as it is based on the wrong dates.

Then there are the known dates of the individual makers. These can be found in my books The standard English pattern or The British playing card industry 1600-2000 and some details are on the plainbacks and wopc websites. The four main British manufacturers have the following dates: De La Rue 1832-1970; Goodall 1820-c.1956, though after 1922 their cards were, in fact, De La Rue products; Waddington 1922-1995, with the No1 brand being continued by Winning Moves; Universal/Alf Cooke 1925-1970. De La Rue became a limited company in 1898 and Goodall in 1897, so any indication of that status (Ltd or Limd) must be after those dates. Note, too, that any pack with Goodall courts and a Waddington AS must be after 1943, when the courts were transferred for printing by the Leeds firm after De La Rue's Bunhill Row factory was destroyed in the Blitz.

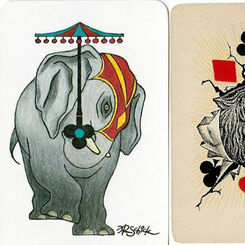

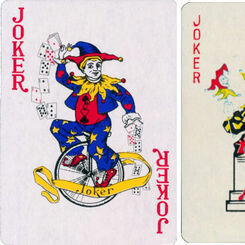

Jokers

I did not deal with jokers in my book, but they can also be useful aids to identification and dating. I give a few examples below.

From top left: 1/2. Obchodni Tiskarny (Czech), the left one is based on a pre-war Piatnik design and was used from c.1935-60, the right one was a close copy of Waddington's design and was used in the 1960s and 1970s.

3. Artex, Budapest, c.1960-70.

Middle row: 4. Waddington's original joker, c.1923-35; 5. Waddington's later design, printed in various versions, still in use today, c.1935 onwards; 6. the Alf Cooke/Universal joker, printed in black and white, c.1925-35, then in three colours c.1935-70, with minor variations.

7. De La Rue's design, used without a frame c.1890-1910, then with a frame. It's found with Goodall courts after the take-over, but seems to have been discontinued by c.1930. 8/9. Goodall, c.1935-55, then in colour, c.1956-70. The original design goes back to the 1880s, but it seems to have been discontinued after Waddington bought out De La Rue.

10/12. A variety of Hong Kong/Chinese jokers, 1980-2014

13. Trefl (Poland), 2014; 14. British Playing Cards Ltd, 1920-25; 15. A Goodall variant with a different arrangement of suits on the upheld card, c.1945-60.

16/17. A couple of jokers by Nascal, Argentina, c.1965; 18. Chinese wide, 2014.

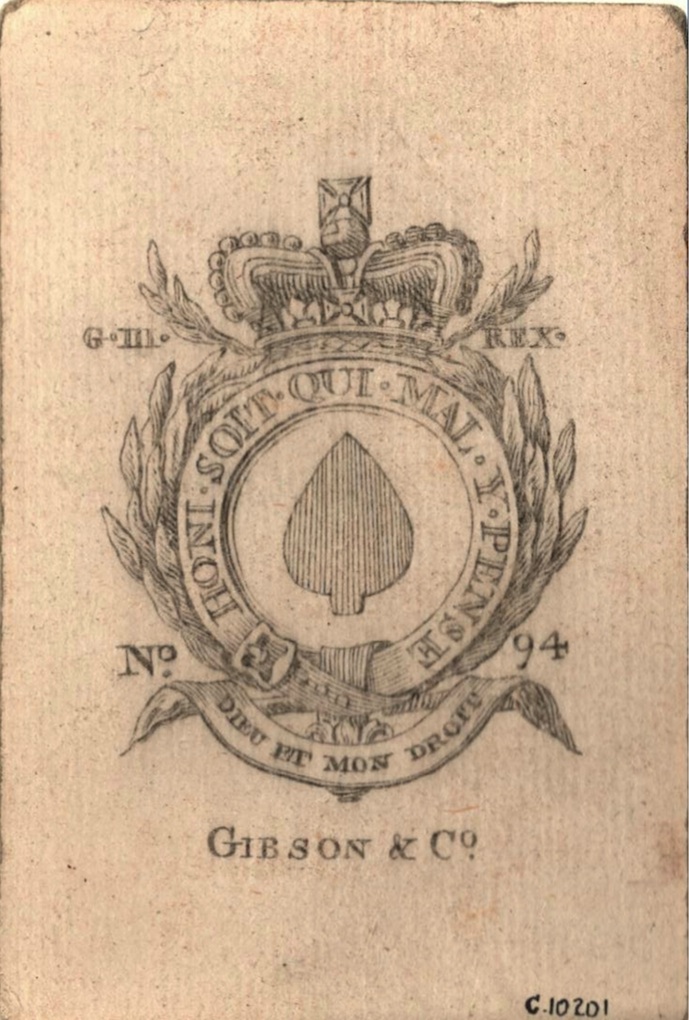

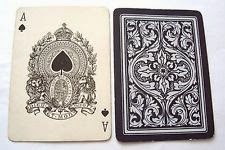

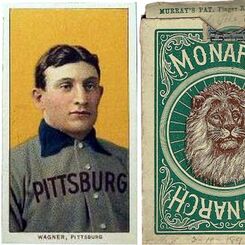

Aces of spades

The details of English makers' ASs are given in my book and on the plainbacks website, in particular, in my contribution to the site on the right of the first page. The AS is always useful, at least for determining chronological windows. On the main part of the plainbacks website you can find dates for the different Garter aces, Old Frizzle and individual makers' ASs. Below I give a few examples of Garter ASs. John Berry put together a scheme for dating the different varieties from the existing records; the full reference to his book is on the plainbacks website. In addition, Paul Bostock and I have included an updated list of early ASs in our book Wood-block & stencil.

Hall (& Son) ASs with Type II courts

Hall (& Son) ASs with Type II courts

Gibson AS with no additional duty indicated, c.1775

Gibson AS with no additional duty indicated, c.1775

Old Frizzle lasted from 1828 until 1862, but within that period it is possible to differentiate on the basis of court card design. For example, the Goodall Old Frizzle below has a double-ended court set (G1.1), so must date from the 1850s.

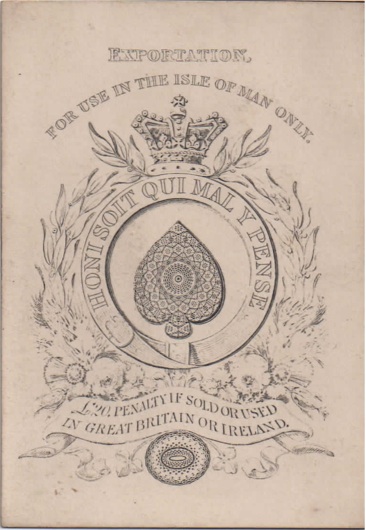

Reynolds' own AS designed after 1862 was modelled closely on Old Frizzle, so do watch out for the differences. One obvious one is MANUFACTURED BY above the design rather than DUTY ONE SHILLING as on Old Frizzle. The one illustrated below is for REYNOLDS & Co rather than REYNOLDS & SONS, which means it dates at the earliest to 1882, when the firm changed its name, shortly before the take-over by Goodall. There is another peculiarity in Reynolds packs: some of their packs use the special unnamed Isle of Man exportation ace of the Frizzle period. With R1 courts this is likely to be from the 1858-62 period, as they were only issued in 1828 and 1858. I thought they were the only firm to use this particular AS, but I now have one with a Whittaker pack, but equally unnamed.

One final note on Old Frizzle: the one printed for De La Rue always had By His Majesty's letters patent printed at the foot. This is a reference to William IV's granting the patent in 1831, but it does NOT mean that the cards are necessarily from his reign. The patent was proclaimed on the De La Rue AS throughout the Old Frizzle period until 1862.

The ASs were part of the taxation system in Britain and tax stamps are another way of identifying cards from other countries, too, though not on the ASs. The USA and all major continental European countries taxed playing cards at various times. Sylvia Mann gives an outline of the main aids to identification in this way in her book Collecting Playing Cards. An important source of further information about taxation, especially in relation to Germany, can be found on Peter Endebrock's website. All the website links referred to on this page can be found on the first page of this blog.

Bridge score cards

In those packs where an extra, bridge-score card has been included, we find a very useful aid to dating. If the pack contains an auction bridge score-card, it is likely to date from before 1928, when the first version of contract bridge scores was introduced. If the no trump score in contract bridge is 35 points, then the pack dates from 1928-32; if the no trump score is 40/30 alternating, then the pack dates from 1932-35; finally, from 1935 onwards the no trump score is 40 for the first trick and then 30 for the rest. Changes to the undertrick penalty scores (not vulnerable) and a score for holding four aces in no-trump hands were made in 1987.

Back designs

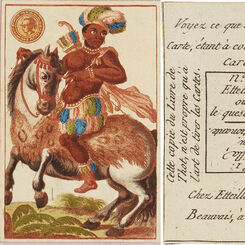

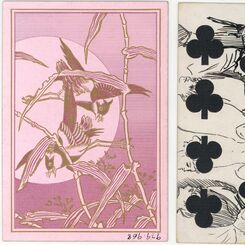

Finally, there are a lot of poor descriptions of backs on eBay. Art Nouveau and Art Deco are STYLES not periods; just because something was designed between 1890 and 1910 doesn't automatically make it Art Nouveau. In fact, Art Nouveau was not as popular in the UK as on the Continent of Europe, and very few card backs were affected by it. Here are two examples from eBay, neither of which are Art Nouveau, but are described as such and incorrectly dated 1890s.

The right-hand pack has 'Limd' on the AS, so can only be after 1897 at the earliest; it was sold by W H Smith on railway stations c.1910.

And here's a pair similarly described.

If you want to know what Art Nouveau is all about, just Google it!

Also, backs from the 1950s often have a flavour of pre-war Art Deco. Again, the fronts of the cards can guide you here: if a Waddington pack has Goodall courts, then it's from the 1950s or later. Waddington took over the printing of all Goodall/De La Rue cards in 1941 after the De La Rue factory at Bunhill Row was destroyed in the Blitz.

For an exercise in dating some Goodall packs, see page 12. For an exercise in dating De La Rue packs with Owen Jones backs, see page 41.

By Ken Lodge

United Kingdom • Member since May 14, 2012 • Contact

I'm Ken Lodge and have been collecting playing cards since I was about eighteen months old (1945). I am also a trained academic, so I can observe and analyze reasonably well. I've applied these analytical techniques over a long period of time to the study of playing cards and have managed to assemble a large amount of information about them, especially those of the standard English pattern. About Ken Lodge →

Leave a Reply

Your Name

Just nowRelated Articles

The Douce Collection

The Douce Collection of playing cards in the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Are Playing Cards a Good Investment?

Playing cards can appreciate modestly, with historical annual gains of 2-3%. Rare cards offer higher...

Luxury Collectable Playing Cards

Luxury packs of cards have been produced since the 15th century, a trend that is very popular among ...

A Case Study

Case Study: using detective work to identify and date a pack discovered in charity shop.

Collecting Playing Cards with Jan Walls

I collected playing cards when I was in primary school, by Jan Walls.

69: My Collection

This is an archive list of my collection. I hope it will be of use and interest to others.

Is Card Collecting an Investment?

“Is Card Collecting an Investment?” - an article by Rod Starling.

Chinese Jokers

Chinese playing card makers have probably produced the widest variety of jokers of any single part o...

A Look Back with Hope for the Future

“A Look Back with Hope for the Future” by Rod Starling

56: Number cards and Chinese Crackers

A brief look at the number cards used in standard English packs.

51: Some modern variations

A brief survey of some current variations in the standard English pattern.

49: De La Rue in detail

A detailed presentation of the variants of De La Rue's standard cards.

Cribbage Board Collection

A collection of antique and vintage Cribbage Boards by Tony Hall

41: A Guide to Dating Playing Cards

Dating is a particularly tricky but very interesting problem to tackle and there are many pitfalls. ...

39: Mixed Packs

A number of mixed packs appear for sale from time to time, but it's important to sort out what is me...

27: Cards at Strangers’ Hall, Norwich

There is a very interesting collection of playing cards held at the Strangers' Hall Museum in Norwic...

15: Perforated Cards, Metal finish and Other Oddities

There are some unusual designs in playing cards, even the shape of the card.

11: Some Cards from Sylvia Mann’s Collection

A fascinating collection that was the basis of a lot of research that we still benefit rom today.

2: Still Collecting Playing Cards at 80

This is a personal account of some of my experiences collecting playing cards.

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 60 days

Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here.

Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here.