Solo Whist

A distinctive British trick-taking game that emerged in the mid-19th century.

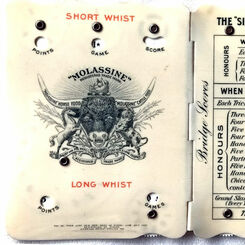

I recently acquired this rather splendid complete box set of cards and counters labelled “Solo Whist”. This got me thinking about a game which I had played in the 1950s and 60s but of which little is heard these days. The cards and the enclosed instructions leaflets identify De La Rue as the manufacturer. As the wrapper shows the penalty for non-cancellation as £20, I conclude that the set dates from the early 1950s. The box includes markers or counters reflecting the 19th century preference for using markers or counters rather than paper and pencils to score card games. This in itself makes the set something of a throwback.

Apart from this new box, my extensive collection of card game boxed sets only includes one other designated for Solo Whist (pictured below) for which, sadly, there are no clues as to origin or date of production. This is a style more familiar to 19th card sets, but I would be guessing.

Readers of my articles will know that I know a lot more about the boxes in which card games were sold than I do about the playing cards themselves. That I have found few boxes specifically identifying Solo Whist is not surprising. As the game is played with a standard set of 52 cards, there is little need for separate boxing, and promotion by special packaging was not a necessary or profitable choice for card game producers.

Solo Whist appears to have its origin in the second half of the 19th century, but it was not until the 1880s that it really took off after which it faded very quickly. Why was it significant? I suggest that this was because it was one of the few whist-style games which involved bidding for contracts. It rose to popularity just as whist players were beginning to experiment with various forms of bidding, and this soon led to the evolution of whist into bridge as we know it today. The details are well documented elsewhere.¹

Unlike whist, which has a huge literature developed over several centuries, Solo Whist arrived relatively late on the scene and while it is included in all the published games compendia from the mid-19th century onwards, there are a surprisingly small number of key texts.

In Jessel², the primary source of information about card game publications in English before 1905, there are only 14 references to texts produced between 1881 and 1902 which are specifically concerned with Solo Whist; nothing is dated as earlier. Of these, most are short articles or monographs, and only three are substantial analyses of the game.

Jessel’s earliest reference to Solo Whist is a 13-page pamphlet published in 1881 in Manchester by John Heywood writing under the pseudonym “Bird’s Eye”.³ Two years later, in Australia, Samuel Mullen published “The Rules of Solo Whist: Derived from the Best Authorities”. Sadly, neither text is available to me in print or online.

The earliest published book on Solo is by Wilks and Pardon in 1888; “How to Play Solo Whist”. This not only presents a “revised and comprehensive code of laws” but it analyses the game in detail and proposes the best ways to play.

I have two editions, the first from 1888 and a second from 1893 which purports to be “A New Edition” but which, as far as I can see, is a complete reprint of the 1888 text. The only discernible difference between the two volumes is that the adverts for the list of Chatto and Windus’s other publications available contained in the last few pages have been updated.

The authors describe Solo Whist as “the great-grandchild of ordinary Whist”. It derived from the American game, Boston which itself was modified in Belgium into a revised form called Ghent Whist. This in turn evolved into Solo Whist which “originally appeared in England, about the year 1856” although “another fifteen or sixteen years elapsed before the game began to be generally known and played in this country”.

Ten years later, in 1898, A. S. Wilks published “The Handbook of Solo Whist”.

His writing partner, Charles Frederick Pardon, had died in 1990⁴, and Wilks was determined to maintain the standing of this earlier work and up-date it. To this end he and his new publisher, John Hogg, acquired the copyright of “How to Play Solo Whist” from Chatto & Windus so that the new Handbook would become the unchallenged source of the rules and information on game play. Consequently, in his introduction the author states: “The leading London Clubs, notably the Victoria, the Albert, and the Beaufort, who in the Solo Whist world occupy a position no less authoritative than does the Portland Club among Whist-players, have accepted and adopted the present code for their guidance, and I venture to hope that it may receive a no less gratifying welcome from Solo Whist circles generally.”

But Wilks was not the only kid on the block! C.J. Melrose, author of “Scientific Whist, 1898”, decided to upstage Wilks with the only other major contribution to Solo Whist publications in the 19th Century, namely “Solo Whist: Its Whys and Wherefores”, 1899. In drafting his revised code of laws, he states that he has “naturally followed in the footsteps of the writers who preceded me and am specially indebted to Mr. A. S. Wilks and to Mr. R. F. Green.” Indebted he may be, but the barbs of rivalry are all too evident. To represent Messers Wilks and Green as equally important is in itself something of a putdown.. Wilks, with Pardon, had been the first to codify the game and write extensively on the subject, promoting its popularity. Green, on the other hand was predominantly a writer on chess but produced a slim volume on Solo Whist in The Club Series of games and pastimes published by G. Bell & Sons. This was nothing more than a brief summary of the game as presented in the original Wilks and Pardon book.

Melrose then goes on through eight pages of introduction to challenge many of the “Laws” proposed by Wilks with obvious distain. He argues “As compared with whist, which has been subjected to exhaustive study and analysis from the time of Hoyle, some one hundred and sixty years ago, the science of Solo Whist may be said to have scarcely yet shed the outer wrap of swaddling clothes. Anything like completeness is, therefore, out of the question without a great deal more experience, observation and thoughtful analysis.”

There is no documented personal feud between these two contemporary authors but clearly, from the style and content of his book, Melrose considers his approach to be superior to that of Wilks. Wilks’ book was practical and instructional, with clear rules for beginners and (as he claimed) for the key London Clubs. Melrose presented his contribution as the comprehensive authority, suggesting that earlier writings (such as Wilks) were too simplistic for serious players. Melrose’s style suggests an attempt to appear to be more authoritative and sophisticated than Wilks and other, earlier writers.

In any event, no matter how these rival sources were regarded at the time, serious card players were already turning their interest towards the new ideas in introducing bidding into traditional whist. By the late 1897s Bridge, in the form of bridge-whist, had started the process of evolution into contract bridge as it is played today.

Tony Hall

12 November 2025

References

- Julian Laderman, Bumblepuppy Days, Masterpoint Press, Canada, 2014

- Frederic Jessel, A Bibliography of works in English on Playing Cards and Gaming, 1905

- There is no reference to John Heywood by name elsewhere in Jessel, and the only entry under the pseudonym “Bird’s Eye” is for the Solo Whist Tract.

- Pardon died at the age of 40 but not before he had worked with Wilks to determine the rules of Solo Whist and become editor of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack from 1887 until his death.

By Tony Hall

United Kingdom • Member since January 30, 2015

I started my interest in card games about 70 years ago, playing cribbage with my grandfather. Collecting card game materials started 50 years or so later, when time permitted. One cribbage board was a memory; two became the start of a collection currently exceeding 150!

Once interest in the social history of card games was sparked, I bought a wooden whist marker from the 1880s which was ingenious in design and unbelievably tactile. One lead to two and there was no stopping.

What happened thereafter is reflected in my articles and downloads on this site, for which I will be eternally grateful.

Related Articles

The Molassine Company and its link to Whist and Bridge

A savvy marketing strategy blending Victorian decorative design with Edwardian practicality.

Scientific Whist

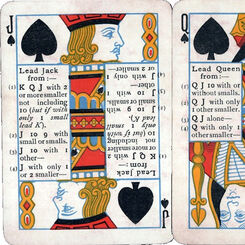

“Scientific Whist” : standard cards with instructions for play on the faces by Chas Goodall & Son, 1...

Agatha Christie and Playing Cards revisited

Agatha Christie uses card-play as a primary focus of a story, and as a way of creating plots and mot...

T. Drayton & Son

Bezique and Whist boxed sets by T. Drayton & Son, London, c.1875.

Dorset Dialect Trails

‘Dorset Dialect Trails’ playing cards, United Kingdom, 2015.

De La Rue Pocket Guides

The 19th Century saw the production, by all of the major companies, of pocket guides or “mini-books”...

The Club Series by G. Bell & Sons

George Bell & Sons produced ‘The Club Series’ of books each specialising in one or more of the popul...

Hoyle v Foster: whose name should we remember?

Hoyle’s name is associated with the rules by which many games are played, particularly card games B...

Hoyle and his Legacy

Edmond Hoyle (1672-1769) was an English writer who made his name by writing on whist and a selection...

A New Look at the Evolution of Whist Markers and Gaming Counters

This article aims to illustrate the evolution of whist and gaming counters from the 18th century to ...

Whist writers and their pseudonyms

Why did so many early writers about whist and other card games feel the need to write under a pseudo...

Whist marker boxes

The Camden Whist marker was being advertised by Goodall and son in 1872 as a new product.

Agatha Christie Playing Cards

Agatha Christie playing cards produced by Planet Three Collection, United Kingdom, c. 2004.

Library Lovers

Library Lovers playing cards published by Word Nerd Games, 2016.

Sixty Penguin Years Playing Cards

In celebration of 60 years of publishing Penguin Books Ltd, 1995.

Dickens Character Collection

Dickens Character Collection published for a London Casino as a promotional gift.

Why do we Collect? My 20 Favourite Items

I suppose people collect for different reasons, rarity, quality, ingenuity of design, sentimental va...

Mary Whitmore Jones and her Chastleton Patience Board

Mary Whitmore Jones and her Chastleton Patience Board by Tony Hall.

Aesop’s Fables

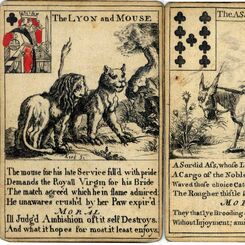

Aesop’s Fables playing cards by I. Kirk, c.1759.

Cribbage Board Collection part 6

A collection of antique and vintage Cribbage Boards by Tony Hall, part 6

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 60 days