Printing of Playing Cards: Letterpress

Some notes on the manufacture of playing cards taken from Thomas De la Rue's patent, 1831.

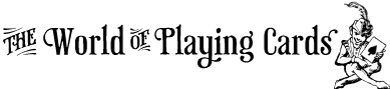

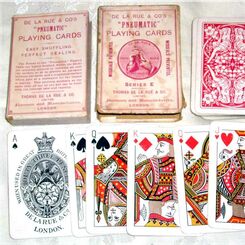

Above: quality of printing in traditional brush & stencil method (top) and De la Rue's new letterpress method (bottom and below).

Some notes on the manufacture of playing cards taken from Thomas De la Rue's patent, 1831

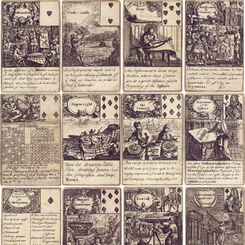

At the time of Thomas de la Rue's landmark Royal Letters Patent for ‘certain improvements in making or manufacturing and ornamenting playing cards’ in 1831, playing cards were stencil-coloured by hand in water colours or printed in one colour and then hand tinted. These processes were time-consuming, laborious and also gave rise to poor quality if the workmanship was careless or imprecise.

The main innovation which Thomas de la Rue introduced was a mechanical method of registering the colour printing so that the different coloured inks were applied with greater precision and did not overlap or be mis-placed as had been the case with stencil-colouring. In addition, quicker drying oil-inks were employed, a new method of glazing the cards by passing them between copper sheets through powerful rollers instead of the antique method of glazing by friction with a flint, and the use of enamelled paper.

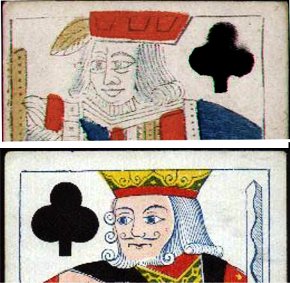

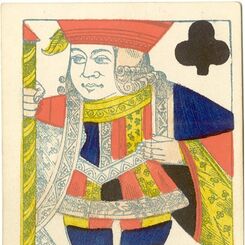

Above: a redrawn set of court cards with more intricate patterns on the clothing, printed typographically, which became the basis for all De la Rue's double-ended court cards. In this case the cards are in the slightly smaller Piquet size, with Continental style suit symbols.

The text of De la Rue's patent includes the following excerpt: “Take one gallon of old linseed oil (the older the better) and boil it very slowly for three of four hours in an iron pot or vessel, occasionally igniting it and stirring during the whole process with an iron ladle. In some instances I find it necessary to dip a few slices of stale bread just prior to ebulation taking place which facilitates the operation... The manner of igniting is as follows: When it is found that by applying a light to a surface it will take fire the pot or vessel is removed from the fire... when it goes out the pot is again placed on the fire - should the ignition be too violent, it must and may be stopped by placing a cover over the top of the pot containing the oil. When cold it should be the consistency of very thick treacle.”.

Notes on the manufacture of playing cards taken from an article published in Bradshaw's, 1842

An article published in Bradshaw's in 1842 contained an account entitled Visit to Messrs De La Rue's Card Factory. “First comes the preparation of the paper, which is subjected to pressure and brushed with white enamel to give it a highly polished finish. Then follows the printing of the playing-card fronts; these are divided into two groups, the ‘pips’, i.e the numbered cards, and the ‘têtes’, i.e. the court cards. The pips are comparatively simple to print: sets of blocks are produced, each containing forty engravings of one card, and as the ordinary method of letter press printing is employed, forty impressions of one card are obtained at the same moment. As the pips bear but one colour, black or red, they are worked together at the hand press... The printing of the court cards is more difficult since they contain five colours. The colours are printed separately and are made to fit into each other with great nicety... for this purpose a series of blocks is provided, which if united would form the figure intended to be produced. By printing successively from these blocks, the different colours fall into their proper places, and the whole process is completed. The printed fronts then go off to the drying rooms for three or four days.”

Above: King of Hearts from letterpress pack manufactured by De la Rue, c.1860. The letterpress 'squeeze' can be seen in the blue outline areas where the ink has been squeezed to the edges, for example around the nose and mouth. The colour areas are superimposed by successively passing the sheet under separate plates which must be accurately aligned or 'registered'.

The backs are printed in the same way. Thomas de la Rue's Jacquard ‘calico’ method is used to produce “repetitive tartan and criss-cross patterns from a single block engraved with straight lines and printed in one colour, which is afterwards crossed with the same or any other colour by again laying the sheet on the block, so that the first lines cross the second printing at any required angle.”

Then the cards are given solidarity. Between the fronts and the backs are pasted two ordinary layers of paper. To be of an especially smooth quality, the paste employed “is cooled by steam, even the pasting performed with a large brush in a series of systematic movements is something of a work of art.” Three of four years were needed to become a master paster, who as early as 1840 could command the ample wage of £2 per week.

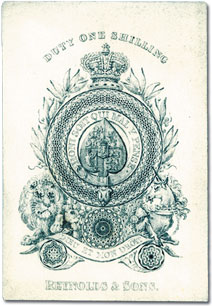

Above: an ‘Old Frizzle’ duty Ace of Spades, c.1840

In quantities of four or five reams at a time the newly pasted sheets of cards are now subjected to the gradual but powerful pressure of a hydraulic press of one hundred tons, which is worked by a steam engine. Any air bubbles between the layers of pasteboard are thus expelled. Again these sheets are carefully hung up to dry to prevent their warping. More pressure is applied to flatten and polish them. If special quality is required the backs are waterproofed with varnish. Finally in order that each finished pasteboard card be of identical size, the sheets are cut into single cards with a big scissors apparatus. By laying up the cards on a long bench, a workman can make up into packs two hundred lots of cards simultaneously.

We also learn from Bradshaw's that the finest quality cards were called ‘Moguls’, the next best ‘Harrys’, and those with imperfections ‘Highlanders’. Tradition has it that the finest, the Moguls, were so called after the Mogul emperors, Harrys were kings - after Henry VIII - and the Highlanders were princes - after Bonnie Prince Charlie.

To ensure that the necessary duty - in 1840 one shilling a pack - has been paid, each ace of spades was printed in the Stamp Office at Somerset House. An account of the numbers of aces was kept there by the authorities.

Towards the end of the 18th century, with the rise of industrialisation, the need for a more powerful source of energy was felt. Steam engines provided the answer, and were employed in playing card manufacture even into the early 20th century.

See also: Amos Whitney's Factory Inventory Chromolithography Design of Playing Cards Make your own Playing Cards Manufacture of Cardboard Manufacture of Playing Cards, 1825 Rotxotxo Workshop Inventories, Barcelona The Art of Stencilling.

By Simon Wintle

Spain • Member since February 01, 1996 • Contact

I am the founder of The World of Playing Cards (est. 1996), a website dedicated to the history, artistry and cultural significance of playing cards and tarot. Over the years I have researched various areas of the subject, acquired and traded collections and contributed as a committee member of the IPCS and graphics editor of The Playing-Card journal. Having lived in Chile, England, Wales, and now Spain, these experiences have shaped my work and passion for playing cards. Amongst my achievements is producing a limited-edition replica of a 17th-century English pack using woodblocks and stencils—a labour of love. Today, the World of Playing Cards is a global collaborative project, with my son Adam serving as the technical driving force behind its development. His innovative efforts have helped shape the site into the thriving hub it is today. You are warmly invited to become a contributor and share your enthusiasm.

Related Articles

English Electric Valve Company Ltd

Special pack made for the English Electric Valve Company Ltd Chelmsford, 1989.

When three brands merge...

After De la Rue factories were bombed in 1940 their cards were printed by Waddingtons. In 1962 Waddi...

Help Yourself Society

The “Help Yourself” Society was formed in 1927 to run fundraising activities for hospitals.

Lincard

“Lincard” card game invented by John William Wolf and patented in 1937.

Vac-tric Electric Vacuum Cleaners

Vac-tric Electric Vacuum Cleaner playing cards manufactured by De la Rue, 1930s.

Pneumatic Series ‘F’

De la Rue Pneumatic Series ‘F’ playing cards, c.1925.

Rūfa

Rūfa is a game designed by Ernest Legh and manufactured by De la Rue. The object is to build a pagod...

Rufford Playing Cards

Rufford playing cards is one of several brand names used by Boots for their stationery department, a...

Hoover Ltd Playing Cards

Vintage cartoon courts and ace of spades specially designed for Hoover Limited, with full colour bac...

Draughts League Medals

Arthur Charles Prince worked for De la Rue as a playing card cutter and later was promoted to superv...

Mathematical Instruments

Mathematical Instruments playing cards forming an instrument maker's trade catalogue, Thomas Tuttell...

Chromolithography

Colour lithography was invented in 1798 by a Bavarian actor and playwright named Alois Senefelder (1...

Printing of Playing Cards: Stencilling

Printing of Playing Cards :: Stencilling can usually be detected by observing the outlines of the co...

Pneumatic Playing Cards

The surface of the cards was slightly grooved by being rolled on prepared plates, so that there were...

Games Leaflets

Thos De la Rue & Co. & Gibson's Games Leaflets.

Swastika designs

Swastika design playing cards by De La Rue, c.1925.

Jean Picart le Doux

Jean Picart le Doux playing cards, issued in 1957 to celebrate the company's 125th anniversary, feat...

De La Rue

De La Rue introduced letter-press printing into playing card production and his patent was granted i...

Amalgamated Playing Card Co., Ltd

Agreement had been reached between Waddington's and De La Rue during the second world war for Waddin...

Carreras Ltd Tobacco Advertising

Carreras issued a number of advertising packs, cigarette and trade cards, miniature packs, etc durin...

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 60 days