78: The Standard English pattern - Part 2, the tricky bits

There are many less straightforward aspects to the designs of the English pattern, which need careful consideration.

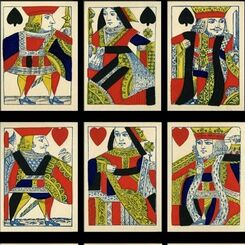

Since the standard English pattern is so widespread, it shouldn't be surprising to discover that some makers have altered the traditional format, sometimes quite considerably. This makes it quite tricky to define the pattern as easily as Part 1 suggests. Take, for example, the way in which turning was carried out by some makers. Hunt's Playing Card Manufacturing Company Ltd, for example, which started up in 1866, had unturned courts with single-ended pip cards, right into the 1880s, when they ceased trading.

Hunt's double-ended courts (H1), 1866-1880

However, when they produced turned courts, they didn't just turn their existing court figures, as necessary, but altered the internal arrangements of the design in some cases.

Hunt's turned courts (H2), in which the three affected queens have been redrawn. The QS has had her sceptre lowered to make way for the suit sign. Interestingly, the KC and JC have had their other hands reintroduced in comparison with H1.

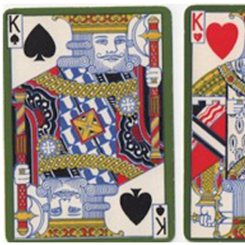

Similarly, the courts produced by Universal from 1925 onwards until they ceased production in c.1970 have altered postures to accommodate the pips. The black kings have also had their head positions switched.

Universal PCCo, c.1930. This design was maintained throughout with slight redrawings and adaptation to the standard width. The QS has had her attributes swapped over and the JC's arrow has been lowered, so he has not been turned. In addition, not determined by turning, the head positions of the black kings have been swapped.

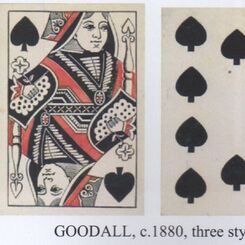

What we now have to consider is to what extent we can include these aberrations within the norms of the standard pattern? Even makers with a tradition in the industry may make inexplicable alterations even when they are not engaged in turning, for example. Goodall, for instance, redrew their courts in the late 1850s and changed the head position of the KS and KH and the JH lost his halberd.

Goodall G2, c.1855-58

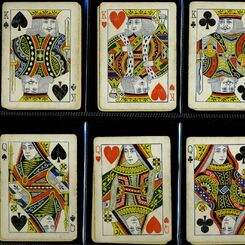

We also have to consider other cases where variation has occurred, as in the American Banknote Company's original courts, used more recently by USPCC, which have 4L (the kings)/8R pips. The JS has been turned and the QH's head has been moved to the left putting their pips on the right.

USPCC, using American Banknote Company courts, from a recent bridge pack, c.1980

A lot of American firms made alterations to the standard postures, turned or unturned, as in the following examples. Some of the results are barely recognizable in terms of the traditional forms.

For some reason Russell and Morgan twisted the head of the JD to face the opposite way, even though they also used the traditional posture in their Steamboat brand.

Russell & Morgan c.1885 with odd JD (US1)

Russell & Morgan with traditional turned posture for JD from a Steamboat pack of about the same date (US1.2)

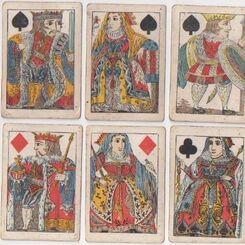

A more extreme example is furnished by firms from the Longley group, where several of the courts have deviant postures.

Chicago PCC, c.1895, with non-standard KC and KD, turned queens and JD, but unturned JC. None of the clothing follows the traditional pattern.

Similar courts from the North American Card Co with different colouring on the clothing and different head postures for the kings. In the other two suits the KH has a non-standard posture and the colouring varies between the two makers.

By the time we get to makers like Offason, it's very difficult to justify categorizing their design as standard English, even though it is marketed under the general trademark of Anglo.

The only court card that has any resemblance to the traditional pattern is the KD, who is in profile.

How do we deal with this in terms of definitions? Since there are a number of elements in the overall definition of a pattern, in particular 12 courts in the case of many European patterns, we must expect fuzzy edges. That is to say that we need to determine the necessary and sufficient criteria of the pattern, which will not necessarily cover every case. It seems perfectly reasonable to state that a pack is of the standard English pattern, except for an odd JD, as in the case of US1 shown above. Equally, we can argue that if a court set has at least five courts with the correct features, then this is sufficient to refer to it as belonging to the standard English pattern, albeit with specified deviation. This would cover the Chicago/North American courts in that the former has three deviant kings and a JD with his attribute on the wrong side and the latter has two deviant kings and the JD. Using this guideline, we can also say that the Dondorf Birmakarte and its double-headed version do not belong to. the English pattern. Not only are there insufficient courts of the right kind, but it can be shown that the figures are better described as deriving from a number of French regional figures.

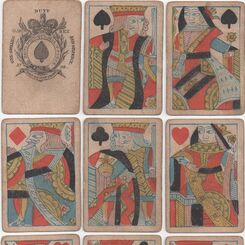

Dondorf Birmakarte

Dondorf for Portugal

The JD in the Birmakarte holds the peculiar attribute found on the English JS, but this is hardly a sufficient criterion to assign it to the English pattern. In any case the figure is a French regional one, the Paris JD as well as the English/Rouen JS. In the Portuguese pack the same figure appears as the JC and the KS holds a sword behind his head like the English KH: again hardly sufficient criteria for an attribution to the English pattern.

For variant versions of the arrangements on pip cards, see page 56.

By Ken Lodge

United Kingdom • Member since May 14, 2012 • Contact

I'm Ken Lodge and have been collecting playing cards since I was about eighteen months old (1945). I am also a trained academic, so I can observe and analyze reasonably well. I've applied these analytical techniques over a long period of time to the study of playing cards and have managed to assemble a large amount of information about them, especially those of the standard English pattern. About Ken Lodge →

Related Articles

77: The Standard English pattern - Part 1, the basics

A simple set of criteria for defining the standard English pattern

Dutch Court playing cards

Games & Print Services’ version of the Dutch pattern.

71: Woodblock and stencil: the hearts

A presentation of the main characteristics of the wood-block courts of the heart suit.

69: My Collection

This is an archive list of my collection. I hope it will be of use and interest to others.

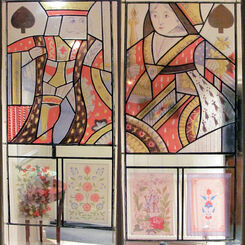

68: Playing cards in glass

My wife and I have recently commissioned a unique pair of stained glass windows for our home.

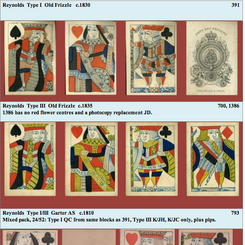

50: Joseph Reynolds

A presentation of my database of Reynolds cards.

49: De La Rue in detail

A detailed presentation of the variants of De La Rue's standard cards.

Hewson

Antique English woodblock playing cards by a card maker named C. Hewson, mid-17th century.

39: Mixed Packs

A number of mixed packs appear for sale from time to time, but it's important to sort out what is me...

35: More Design Copies

Here I want to take another widely copied design and see how individual variation by the copier can ...

Suicide King

The King of Hearts, holding a sword behind his head, is sometimes nicknamed the “Suicide King”. He c...

33: Functional Changes to Playing Cards

The emphasis throughout my collecting has been on the design of the courts cards, and it should be p...

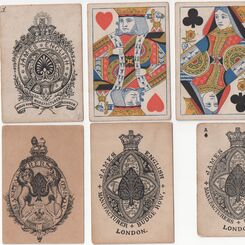

29: James English

An overview of the courts and aces of spades produced by James English

17: Waddington, Including some of their Less Common Packs

John Berry's two-volume work on the Waddington archive and collection is a very comprehensive presen...

6: Some Non-Standard Cards

I only collect the English standard, but I thought it would be a good idea to add some different typ...

5: De La Rue

In December 1831 Thomas de la Rue was granted his patent for printing playing cards by letterpress.

2: Still Collecting Playing Cards at 80

This is a personal account of some of my experiences collecting playing cards.

Traditional English Court

Games & Print Services Ltd traditional English courts.

History of Court Cards

The court cards in English packs of playing cards derive from models produced by Pierre Marechal in ...

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 60 days