Regional Cards: China and Hong Kong

Explore the history, patterns and designs of traditional Chinese playing cards, featuring unique regional variations.

Chinese and Hong Kong Cards

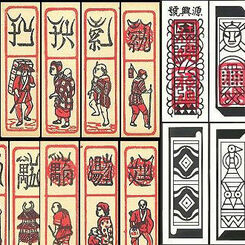

In China several traditional cards exist, most of which are still in use, especially in the provinces located along the coast. Most of the packs are made of a larger number of cards than the European ones. They might look peculiar to Western eyes, both for their dimensions, usually thin and long, thus quite smaller than Western ones, and for the variety of illustrations and personages they feature.

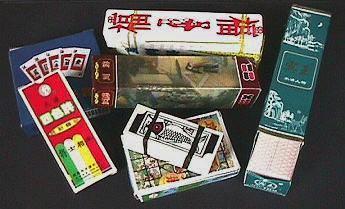

Above: Assorted traditional Chinese playing cards in various packaging styles, including paper wraps and boxes.

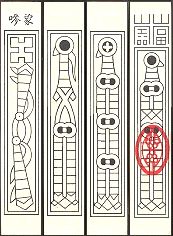

The reason for such a narrow shape is very likely the use of holding many cards in hand at the same time, overlapped in a "vertical" arrangement (i.e. not in "fan" position), so that one of their ends remains visible: their indices, where present, are consistent with this arrangement, being located at both ends of the cards.

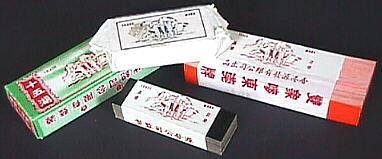

Above: Traditional Chinese playing cards, narrow and elongated, used for holding multiple cards vertically. These decks often contain over 150 cards and often feature a larger number of cards compared to Western decks, with distinctive illustrations.

Another typical feature rarely encountered in Western cards is that, with few exceptions, the subjects of a Chinese deck are duplicated several times (how many times depends on the pattern or even on the different editions), and this explains how some decks may contain over 150 cards.

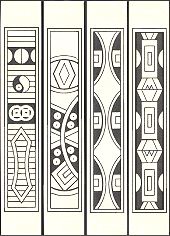

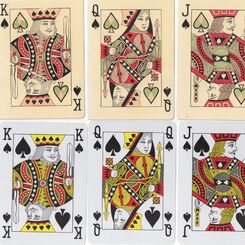

Their backs, instead, are more often plain, i.e. of only one colour, but some patterns do have geometric motifs, in a more Western fashion.

Historical Notes

China is the country in the world where playing cards were first created, probably hundreds of years before they reached Europe, but the scarce sources available and the inevitable linguistic difficulties give reason for many gaps still left in the history of early Chinese cards.

At the end of the 19th century, anthropologist S. Culin and sinologist W. H. Wilkinson investigated the patterns extant by those times, and compared them with earlier decks and single cards found in museums and collections (the pictures shown along the historical notes are original illustrations taken from a publication by Wilkinson dated 1895). Their reports clearly show that playing cards in China have not developed in time as much as they did in Europe, and that their suits and subjects have remained substantially unchanged.

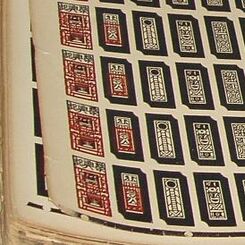

Many decks are sold either wrapped, or bound together by a strip of paper with the company's name, or even tied with a string, as shown in these pictures. A cardboard box too is sometimes used.

The Chinese patterns may be grouped into a number of main families, known as money-suited cards, chess cards, domino cards and character cards, according to the kind of suits and to the structure of the deck.

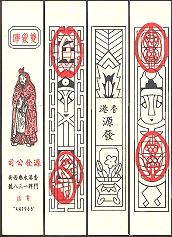

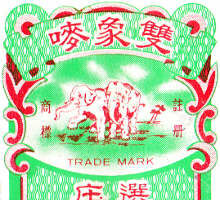

Above: brands of traditional Chinese playing cards from south-eastern China and Hong Kong, designs featuring fish, elephants, and eagles are commonly seen on packaging.

However, these are Western names and do not correspond to the way Chinese players refer to them; furthermore, even within one same group each of these patterns should be considered individually, because the number of cards they are made of, the geographic area they belong to, and the games played with them are different.

Since the literal translation of the names of decks, suits and single cards in Chinese does not always match their Western equivalent, both the original version and the less "exotic" one (provided the latter does exist) are reported in the text.

Lastly, a note of folklore. The Cantonese have a saying: good things come in pairs. This is clearly reflected by the names of the brands and the decorative details featured in couples by several cards, an element of good luck that characterizes decks from the south-east of China and Hong Kong (as seen in the picture on the right).

Domino Patterns

Right: an illustration from a traditional Chinese domino card, featuring a seated figure, used in games derived from domino sets.

The popular variety of cards featuring black and red dots sprang from domino sets, or  Ku Pai ("bone tiles") in Chinese, whose pieces were - and still are - quite similar to the Western ones.

Sometime around the 12th century (a rather approximate dating), decks made of pasteboard began to appear in place of the usual ones, of bone or ivory.

Ku Pai ("bone tiles") in Chinese, whose pieces were - and still are - quite similar to the Western ones.

Sometime around the 12th century (a rather approximate dating), decks made of pasteboard began to appear in place of the usual ones, of bone or ivory.

Although this may sound strange, the Chinese make little distinction between "tiles" and "cards", the latter simply acting as an alternative shape of the former, so that both of them are referred to as pai, a generic word for labels, tiles, cards, tags, etc.

Unlike actual tiles, though, Chinese domino cards developed through the ages into different patterns, according to the number of duplicate subjects for each combination of dots and to the size of the cards (ranging from very small to rather large).

Money-Suited Patterns

Another early pattern is known as  Gun Pai ("stick cards" or "cane cards"), likely referring to their shape. Wilkinson maintained that these cards were created from early books, whose pages were made individually detachable for an easier reference; later on, their use as an amusement would have caused their size to be reduced. According to his theory, this kind of books came into use in China by the mid 8th century; if this proved correct, the Gun Pai might have been created before the domino cards.

Gun Pai ("stick cards" or "cane cards"), likely referring to their shape. Wilkinson maintained that these cards were created from early books, whose pages were made individually detachable for an easier reference; later on, their use as an amusement would have caused their size to be reduced. According to his theory, this kind of books came into use in China by the mid 8th century; if this proved correct, the Gun Pai might have been created before the domino cards.

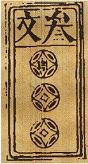

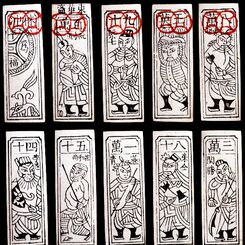

Left: an early 9 of Myriads card from the antique Chinese Gun Pai pattern, depicting stylized figures and characters, used in traditional money-suited card games.

The structure of this pattern was described as based upon three suits, whose cards featured signs from 1 to 9 (but one suit had numerals). The suits were identified by Wilkinson as

As an alternative name for these cards, Wilkinson's report mentions

Despite the shape, the length, the graphic style, the use of indices, etc. of old Gun Pai decks appear rather heterogeneous, they belong to one same pattern, the ancestor of the three-suited Chinese and Vietnamese money cards now extant.

Right: an early 3 of Coins (or Cash) card from a traditional Chinese deck, featuring stylized coin symbols, used in money-suited card games.

Lastly, both Culin and Wilkinson described a third early pattern, labelled by the latter author with the Cantonese name of

Also these cards featured values from 1 to 9. Wilkinson specified that the 1s of both the highest and lowest suits were called "100 children" and "ace of Coins".

Two more subjects belonged to the pack: one of them matched the Gun Pai's "White Flower", and the other card likely corresponded to the "Red Flower". All the 38 cards of these packs were single (no duplicated subject).

Today's Hakka cards, and the Vietnamese Bâ´t deck, described in Regional Cards: South-East Asian, practically have the same composition.

It is not possible to define whether the Gun Pai or the Lat Chi was the original pattern from which the other one sprang in a second time, but there is little doubt that they shared a common ancestor.

Recently, scholar A. Lo reported sources from the mid 15th century and the late 16th century in which two four-suited patterns, one with 38 cards and one with 40 cards respectively, are described in detail. The first one matches Wilkinson's Lat Chi; the 40-card deck, instead, has two additional subjects, and is referred to as for the game of Ma Diao, whose phonetic resemblance with the aforesaid Ma Que (or MahJong) is likely not a coincidence.

The Turfan Card

Above: the location where the card was found

The oldest known Oriental playing card was found in 1905 in XinJiang province (Central Asia, presently nort-western China), by an archaeological site near the city of Turfan, whence its present name. It is now held by the Staatliches Museum für Volkerkunde, in Berlin (Germany).

Above: the Turfan card, the oldest known Oriental playing card, featuring a stylized figure and used in early money-suited card games.

Unfortunately, the age of this card cannot be assessed, although it is believed to be several centuries old. It might even be the oldest extant in the whole world, but no evidence supports this claim. Therefore, this specimen tells us much more about where such cards were used, rather than when this happened.

Whatever age it may belong to, the striking resemblance with some of the subjects found in modern money-suited decks indeed suggests a connection; the stylized faces featurd on such cards represent the personages of a popular novel called The Water Margin (Shui-hu Zhuan). The same personages are also commonly borrowed by other types of playing cards, particularly the Chuan Pai (a Chinese domino card variant) and Poker decks, in which their full figures are used as decorations in the central part of the card. The novel itself may provide a clue for the dating: it was written in the 14th century, and considering that some further time should have elapsed before its personages became renowned throughout the country, we may speculate that these faces should have not appeared on Oriental playing cards any sooner than during the same century, or eventually later. But this time limit would only be correct in the case the portrayed subject really was a character from The Water Margin.

The Turfan card is consistent with the subject found in money-suited decks called Red Flower (see details in the following paragraph), and also the shape of the card seems to match that of modern Chinese decks.

Another unsolved question is "where did the card come from?".

In fact, in XinJiang province, once Chinese Turkestan, the language spoken was (and still is) Uyghur. Originally, it was spelt with an archaic script called Orkhon, then replaced with the Arabic one in the 16th century, and finally in the 20th century with both Western and Cyrillic alphabets. Chinese glyphs, such as the ones featured at both ends of the card, were never used. Therefore, this specimen may have come to Turfan from further east, maybe left behind by soldiers or by merchants; elseways, it may be the proof of a very early pattern, but already popular up to the point of being known in Central Asia, whose design (including the glyphs) would have remained steady, regardless of the geographic area where the cards were printed and/or used.

Money-Suited Cards

Above: Southern China and Hong Kong.

Money-suited cards is the name given to the most important group of Chinese patterns. It was inspired by the old local coins, to which the graphic look of the suits is related. These patterns are popular especially in the regions along the country's central and southern areas (see map). The main features of the group are:

Above: the old Chinese Cash that inspired the money-suited system.

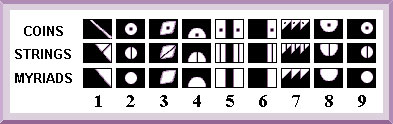

- three suits, given the Western names of Coins, Strings and Myriads;

- values running from 1 to 9, plus a number of honour cards, of higher rank;

- some decks also have one or more special subjects.

Also a few 4-suited patterns, such as the Hakka cards and the Vietnamese Bâ´t cards, belong to the money-suited family.

- Coins suits in this group usually feature a stylized pattern related to old Chinese coins (the ones with a square hole in the center). The name of such coins, Cash, is also alternatively used to indicate this suit.

- The Strings, instead, show these coins threaded up on a string, as Chinese people used to carry them (i.e. a striped pattern represents these threads as seen from aside). Symbolically, Strings are equals to 100 coins.

- the cards of Myriads have stylized patterns inspired by The Water Margin (Shui-hu Chuan), a well-known 14th century fictional story written in Chinese vernacular language.

Above: the wan (or man) character, in ordinary and official spelling.

Above: the shape of signs in different money-suited patterns.

Myriads are the only cards whose values are not stated by the number of suit signs (or pips), but by Chinese numerals from 1 to 9. The name of this suit comes from the character wan (or man in Cantonese dialect), meaning either "ten thousand" or "myriads, multitude", which in some patterns appears next to the value's numeral.

Since all Chinese numerals can be spelled in two forms, the ordinary one and the official one (more elaborate), in the cards of Myriads the number expressing the value is always found in ordinary form, while the suit character (wan) can be found in either of the two, as shown on the left.

Above: Guan.

In other card patterns, instead, the sign of the Myriads suit is a different character, guan (Cantonese gun), shown on the left, whose literal meaning is "to pierce, to pass through", but also meaning "a string of 1,000 coins".

In spite of being different characters, these two may be considered as "interchangeable" signs for the same suit. In fact, Wan is used in short for "10,000 Guan" (i.e. 10,000 x 1,000 coins, or 10 million coins). Furthermore, the suit of Guan is referred to as Wan by players, and these two signs (or suits) never appear in the same deck.

In four-suited patterns (such as the Chinese Hakka or the Vietnamese Bâ´t) there is a further suit of higher rank, named Tens, which actually means "tens of myriads" (i.e. 100 million coins).

Such a numerical interpretation of the suits is proven by the rank they have in some games, which goes from Tens (if present) or Myriads (either Wan or Guan) to Strings, down to Coins, i.e. single units. Only Mah Jong suits partially diverge from the aforesaid scheme (see table on the right and relevant paragraph further down in the page), but the signs adopted still show a graphic resemblance with the traditional ones, having sprung from the latter.

Doug Guan Cards

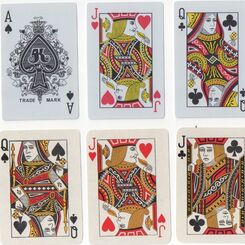

Note: all DongGuan cards shown come from a Double Elephant Brand edition, by Guan Huat (Hong Kong).

Above: GuangDong province.

The name of this pattern simply means "DongGuan cards" (referring to a town in the province of GuangDong, southern China.)

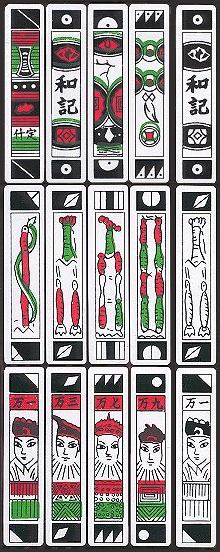

The deck contains 124 cards, divided into three suits named Wen, Suo and Wan, equivalent to the aforesaid Coins, Strings and Myriads.

Above Left: 1, 5 and 9 of Wan (Myriads). Above Right: 2, 3, 7 and 9 of Suo (Strings) from a traditional Chinese deck.

In this pattern the suit of Wan (Myriads) is shown by means of the character guan, previously described, though its name has remained unchanged. It features very stylized faces, representing personages from "The Water Margin", as explained in the introduction. The values of these cards run from 1 to 9. The 9 of Strings is different from other subjects because it features a red stamp (or seal).

From left to right: Gui card (Ghost), Da Hong (Old Thousand), Ba Shu (White Flower), and Xiao Hong (Red Flower) from a traditional Chinese deck.

This deck also has three additional or honour cards named Da Hong ("big red"), Xiao Hong ("small red") and Ba Shu ("eight bundle"), probably referring to the eight chevron-like elements in the upper part of the card. Other known names for these cards are Old Thousand, Red Flower and White Flower, respectively. The first two of them feature a couple of red stamps, similar to the single one featured by the 9 of Strings; the White Flower instead has no stamp and shows a stylized white flower in a pot.

The masque-like pattern featured by both the Da Hong (a.k.a. Old Thousand) and the Xiao Hong (a.k.a. Red Flower) has graphic resemblance with the cards belonging to the Wan (Myriads) suit: in fact, also these ones represent personages from the same epic novel. There is a further special card in the deck, named Gui (Cantonese Gwai), meaning "devil" or "ghost", featuring a small male figure that wears traditional Chinese clothes. This is the only subject whose illustration is not in black & white, except the red seals, and its purpose is that of the special loose cards in early Gun Pai decks (see the historical notes).

Above: 1, 4, 6, and 9 of Wen (Coins), featuring stylized patterns representing old Chinese coins.

In the DongGuan deck, each of the cards mentioned above is repeated four times.

While in the Wan (Myriads) suit values are indicated by numerals, in the other two suits this is shown by pips. To a westener's eye, some of these arrangements might be difficult to read. In the Strings suit, for instance, what has to be counted is the number of "ladder-like" or "railway-like" stripes, which represent threads of coins, as mentioned above in the introduction; the 9 of this suit does not follow this criterium, but it can be easily told all the same because of its red stamp (see previous picture).

Also values shown by the Coins suit are not so easy to read, as the illustrations are very stylized, and in most cards only a section of each coin is shown.

DongGuan cards are used for playing DaFu and QuanDui; rules for the latter game can be found in the relevant page of John McLeod's website.

Money-suited cards found in various parts of China comply to less strict schemes than Western patterns; in fact, although all packs have traditional suits, with pip cards from 1 to 9, the number of times each subject is duplicated and the quantity and illustrations of the special cards (if any) are subject to changes.

Above: ZheJiang province.

Furthermore, these decks are often manufactured and marketed on a local basis (up to recent times, in China there was no company large enough to print and sell cards all over the country). Therefore, it is not unlikely for some patterns to bear more than one name in different parts of China, while other patterns do not even have a specific name, being generically referred to by the local players as "cards", "paper cards", or other generic names of the like.

This is the case of the pattern featured in the following pictures, that comes from the province of ZheJiang, merely labelled as "plastic cards for amusement".

The deck contains the same subjects as the aforesaid DongGuan pattern, including Old Thousand, Red Flower and White Flower, but in this case each card is repeated five times instead of four.

Above: Coins (top row), Strings (middle row), and Myriads (bottom row) cards, showcasing traditional designs and vibrant colors.

Above: Old Thousand, Red Flower, and White Flower cards, featuring colorful illustrations and traditional motifs.

There are also five special subjects featuring human figures, whose names read the Major, the Minor, Money, String and Myriad (the last three evidently refer to the suits which, however, they do not belong to). A sixth special card has no human figure but a rather large vertical text, merely a certification of the product's quality ("meeting the standard"). These six subjects, shown at the bottom of the page, are single.

Above: note how Coins and Strings differ from Myriads by tiny graphic details (dots, lines), that somewhat recall the shape of the suit.

All together, the cards in the deck are 156. Out of five sets, two of them and the six special cards are illustrated in colour, while all the other ones are in black and white. Samples of the latter are shown in the picture on the left (i.e. the card to the far right in each row).

On both ends of each card is a small black rectangle with a white pattern inside: these are indices, from whose shape both the value and the suit of the card can be told. The system is shown in full in the diagram below.

Above: special cards from a traditional Chinese deck, including the Major, the Least, Money, String, Myriad, and King Card, featuring colorful illustrations.

Similar index systems are used by other money-suited patterns (see also Regional Cards: South-East Asian).

Instead, the Old Thousand, the Red Flower and the White Flower, as well as the special subjects, feature different indices. The latter have them in yellow; among them, the top index of the "meeting the standard" subject reads "king card".

Besides the use of coloured subjects, other unusual details are found in this pattern. For instance, the absence of red stamps on the Old Thousand, Red Flower and 9 of Strings. One more curious feature is the graphic look of the Strings suit: the 3-dimentional rendering of the coins strung together is somewhat reminiscent of the cudgels in the suit of Batons belonging to the central-southern Italian and Spanish cards.

Also the faces of the personages in the suit of Wan, yet naive, are less stylized than the ones found in the DongGuan pattern.

References & Notes

- Due to romanization (i.e. the spelling of Oriental words in Western letters based on their original sound) some names might have different versions. In these pages the standard system presently used (Pinyin) has been adopted, including some names quoted from the works of other authors.

- For some names the original Chinese spelling is also shown. Since Mandarin is the official language of the country, though many playing cards are from areas where Cantonese, Hakka and other dialects are spoken, the names are given in their most common form.

- My thanks to Jeff Hopewell, ChungPang Lai, John McLeod and Dylan W.H. Sung for their precious help.

By Andy Pollett

Member since June 10, 1999

For almost one thousand years, in every part of the world, playing cards have been one of the most common pastimes. As a collectable item, instead, they are indeed less popular.

An amazing number of different varieties exists, surely many more than even the most experienced card players would ever imagine. There are decks with special illustrations in place of the usual courts, but others, used in some parts of the world, also have different suits in place of the ones most people are accustomed to. And some decks do not even have suits: according to the games they were created for, they may have numbers, or other special illustrations.

These pages discuss in depth most topics concerning playing cards, with a particular interest for their history, and the many patterns used in different countries, the obsolete ones as well as the varieties still used. The picture galleries, organized by type and by geographical distribution, present several examples of the varieties extant, providing at the same time an extensive description, yet easily understandable also for first-timers.

Leave a Reply

Your Name

Just nowRelated Articles

Chinese Money-Suited Playing Cards from the British Museum

This deck of Chinese playing cards, donated to the British Museum in 1896, is believed to have been ...

Characters of “The Water Margin”

Characters from the Chinese novel “The Water Margin” - 水滸撲克.

57: China 3

A third and final look at some Chinese cards.

Hakka

“Double Happiness” brand Hakka [客家] playing cards used by Hakka ethnic communities who have a separa...

54: China 1

Although many people would not consider Chinese cards worth collecting, the huge variety of court de...

Terracotta Army

Each card has a different photo of elements of the terracotta army whose purpose was to protect the ...

Magic Poker Cards

“Magic Poker Cards” are often found inside Christmas crackers along with party hats, puzzles and jok...

Terracotta Warriors of Emperor Qin

“Terracotta Warriors of Emperor Qin” collectible playing cards, made in China, c.2010.

Chi Chi Pai

Chinese “Chi Chi Pai” Playing Cards by Mesmaekers Frères for Far East market.

Titicaca ® Playing Cards

Each card in this novelty deck, subtitled “Funny Card”, carries information about a prestigious or p...

Mad Jack Miracle Pack

Mad Jack Miracle Pack by Chu’s Magic (Tobar) 1999.

Li River Souvenir

Li River Souvenir Playing Cards from China.

Hong Kong

A large proportion of the world's souvenir and pin-up playing cards originate from Hong Kong.

Plants vs. Zombies UNO Card Set

Plants vs. Zombies UNO card set Chinese edition, licensed by Mattel East Asia Limited, 2011.

Mahjongg

Mahjongg is usually played with tiles, which are Chinese playing cards made in solid form...

Playing Cards from Malaysia

Playing Cards from Malaysia.

Double Elephant & Double Dragon

Double Elephant brand Four Colour cards

Thai & Siamese Playing Cards

The Portuguese were the first Westerners to trade with Ayutthaya in Thailand in the 16th century. Tr...

Regional Cards: South-Eastern Asia

Indonesia • Malaysia • Singapore • Thailand • Vietnam

Chinese Playing Cards 中国纸牌

The Chinese took their cards with them wherever they travelled and traded in the East, and we find C...

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 60 days

Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here.

Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here.