History of English Playing Cards & Games

The History of English Playing Cards dates probably from the mid 15th century

Right: Detail from painting of Elizabethan Card Players, illustrated in "What Life Was Like in the Realm of Elizabeth: England AD 1533-1603", Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1998, pp. 40-41

THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH PLAYING CARDS dates probably from the mid 15th century, the first documentary evidence of their existence in this country occurring in an Act of Parliament [3 Edw. IV. c.4] which, upon the petition of domestic card makers, prohibited the import of foreign cards. Some 20 years later, we learn from the Paston Letters that the family played cards on a festive occasion. Court accounts during the reign of Henry VII refer to the Queen's debt at cards. But still we have no direct evidence of what the cards themselves looked like.

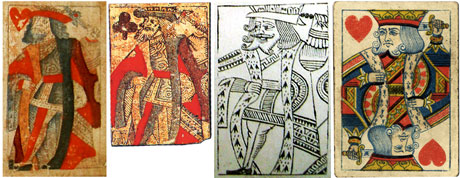

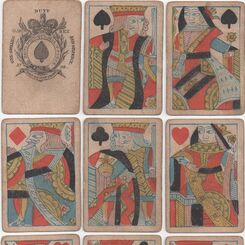

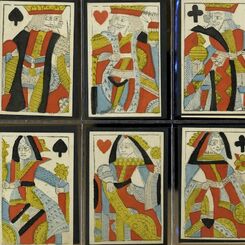

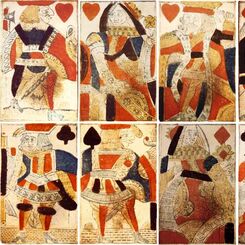

Above: four cards showing how modern anglo-american playing cards evolved from late fifteenth century French cards. The so-called 'Suicide King' originally held an axe.

Cards made in Rouen at that time were an eclectic mixture of features from cards made for various foreign markets, hence the origins of what became the "English" pattern are not one precise source, but a mixture of several earlier regional patterns.

Other examples of early Anglo-French cards also show details which appear in English cards.

It seems reasonable to suppose that they resembled the earliest designs which we know to have come from France (see illustrations right), which have subsequently evolved into the English pack. Designs by Valery Faucil of Rouen (c.1500), by Jehan Henault of Antwerp (1543) or by Pierre Marechal of Rouen, made some 20 years later, are known. Other early cards exist in museums and libraries.

These designs probably originated in the city of Rouen, where cards were made and exported to many parts of Europe. French suit marks were employed, but when the English came to name the suits we find Spanish or Italian influences which leave us no clearer on the matter… the nomenclature is highlighted by the popularity in the past of such imported games as Ombre and Primero.

By their nature and use, cards are flimsy and perishable. If players do not wear them out, then mice will eat them. It is hardly surprising that the total number of English cards surviving before 1590 cannot exceed a dozen or so.

In 1590 an educational pack of cards was made by William Bowes illustrating county maps of England and Wales. Cards from about 1630 were found in the walls of Trinity College Cambridge, early in the 20th century.

In the mid-17th century the Puritan regime was doubtless responsible for the destruction of thousands of packs, gambling being regarded by half the country as frivolous and immoral, although the manufacture of cards was permitted. Thousands of packs must also have been destroyed during the great plague of London (1664-1666) and in the Great Fire of London (September 1666). It is not until the restoration of Charles II that we find any sort of order and continuity in the history of the publication of playing cards, or, indeed, surviving examples of full packs.

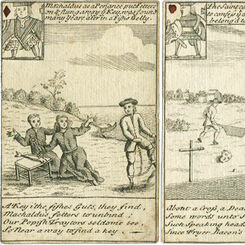

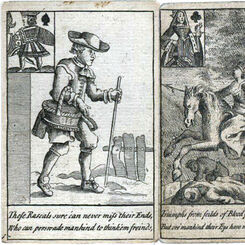

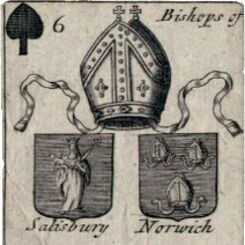

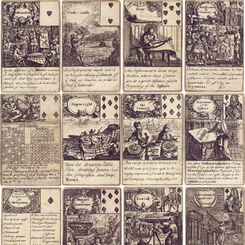

It is therefore with this period that collectors begin to feel involved, although 17th century cards are very rare. The standard cards of the period, that is to say those traditionally used in play, are almost the most elusive of all, probably having been used to the point of disintegration and then thrown away. But by this time card makers had discovered new markets and uses for cards presented in novel form and issued many pictorial packs with the purpose of entertainment, education or propaganda of one kind or another. (Illustration to right: Heraldry card from Arms of the English Peers pack, 1686 / Card from 17th century English Proverbs pack.)

During the early 17th century a group of manufacturers banded together in London and with the King's support formed the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards in 1628. The King was desperate to raise money to continue fighting his wars and so, in exchange for tax revenues, he granted charters of incorporation to a number of trade guilds. Sums of money were paid for each concession and dues were yielded upon each year's trading.

The intention was to prevent the entry of foreign cards and to control and supervise manufacture within the London area. The Worshipful Company collected the tax on each pack sold and this was paid to the King. The revenue collected equated to the amount lost from the banning of imported cards, and at the same time the cards were no more expensive than they had been during the previous years.

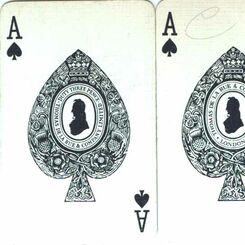

After 1712 each pack had to be stamped or marked with the maker's name. As a result the appointed Commissioner for Stamp Duties chose the Ace of Spades to receive the mark and it remains so to the present day, although the actual duty was abolished in August 1960 as it had become uneconomical.

Excerpt from: Henry Mayhew's “London labour and the London poor”...

The sale of playing-cards is only for a brief interval. It is most brisk for a couple of weeks before Christmas, and is hardly ever attempted in any season but the winter. The price varies from 1d. to 6d., but very rarely 6d.; and seldom more than 3d. the pack.

The sellers for the most part announce their wares as "New cards. New playing-cards. Two-pence a pack." This subjects the sellers (the cards being unstamped) to a penalty of £10, a matter of which the street-traders know and care nothing; but there is no penalty on the sale of second-hand cards. The best of the cards are generally sold by the street-sellers to the landlords of the public-houses and beer-shops where the customers are fond of a "hand at cribbage," a "cut-in at whist," or a "game at all fours," or "all fives." A man whose business led him to public-houses told me that for some years he had not observed any other games to be played there, but he had heard an old tailor say that in his youth, fifty years ago, "put" was a common public-house game. The cheaper cards are frequently imperfect packs. If there be the full number of fifty-two, some perhaps are duplicates, and others are consequently wanting. If there be an ace of spades, it is unaccompanied by those flourishes which in the duly stamped cards set off the announcement, "Duty, One Shilling;" and sometimes a blank card supplies its place. The smaller shop-keepers usually prefer to sell playing-cards with a piece cut off each corner, so as to give them the character of being second-hand; but the street-sellers prefer vending them without this precaution. The cards - which are made up from the waste and spoiled cards of the makers - are bought chiefly, by the retailers, at the "swag shops."

Playing cards are more frequently sold with other articles - such as almanacks - than otherwise. From the information I obtained, it appears that if twenty dozen packs of cards are sold daily for fourteen days, it is about the quantity, but rather within it. The calculation was formed on the supposition that there might be twenty street playing-card sellers, each disposing (allowing for the hinderances of bad weather, &c.), of one dozen packs daily. Taking the average price at 3d. a pack, we find an outlay of £42. The sale used to be far more considerable and at higher prices, and was "often a good spec. on a country round."

Excerpt from Henry Mayhew's "London labour and the London poor", first issued (serially) in the 1840s, but in 1851 the work was re-issued in three volumes. Information courtesy Anthony Lee.

Before 1880 playing cards had no numbers in the corners. This had always created a problem when trying to fan out the cards. Also, the court cards were single-ended, full figures, so an opponent might notice the presence of a royalty in hand if it was to be placed right-way-up.

Until Victorian times in England the backs of playing cards were plain, but eventually designs had to be printed on the reverse to avoid card sharps with a keen eye from recognising a card from the soiling or dirt marks on the back. Wear and tear during play resulted in the square corners becoming scuffed and rounded, and so round corners became standard.

Finally, the 53rd card in the pack was introduced at the end of the 19th century by the Mississippi gamblers on the river boats in America, and the pack evolved into the pack of cards that we take for granted today.

Cards of the past all belong to and evoke their period, whether it be a matter of style, fashion or customs. They belong to a cheerful, gregarious, competitive world, and provide the collector, by their associations, with an unusually vivid view of history, nonetheless interesting for being from the sidelines.

THERE IS A MAGIC IN GAMES… from those created in the imagination, such as hide and seek, to those using pieces of paper, sticks or sophisticated manufactured items. Some games recreate the thrill of sporting activities, whilst others give a sense of creativity. A few can even cause anger and frustration.

Children's card games have been somewhat neglected in the past. They are distinct from ordinary playing cards, with their most obvious difference being the lack of any court cards or suit marks. Instead game cards are either numbered, lettered or grouped in some other way.

Children's card games used to be produced to very high quality, both in the materials used and the design and printing. Economic circumstances change, and children's card games today vary in quality and educational value.

Children's card games used to be produced to very high quality, both in the materials used and the design and printing. Economic circumstances change, and children's card games today vary in quality and educational value.

Cards specifically designed for the amusement and education of children did not appear until the second half of the 18th century. Those produced at this time tended to have pictorial themes rather than the numerical format we are familiar with today.

A huge variety of games has been devised over the years, the best known of which are Happy Families or Quartet games which involve completing sets of cards and declaring these to win the game. However, cards have also been used to tell fairy tales, ask and answer questions, illustrate nature, animals, places, to teach foreign languages, to foster early learning with numbers, spelling, currency, telling the time, and so on.

Learning the ideals of good behaviour came to be regarded as important as the three Rs: the precepts were often found as proverbs or morals on cards, just as they were reproduced in the handwriting copy-books of the day and preached from the pulpit.

By Simon Wintle

Spain • Member since February 01, 1996 • Contact

I am the founder of The World of Playing Cards (est. 1996), a website dedicated to the history, artistry and cultural significance of playing cards and tarot. Over the years I have researched various areas of the subject, acquired and traded collections and contributed as a committee member of the IPCS and graphics editor of The Playing-Card journal. Having lived in Chile, England, Wales, and now Spain, these experiences have shaped my work and passion for playing cards. Amongst my achievements is producing a limited-edition replica of a 17th-century English pack using woodblocks and stencils—a labour of love. Today, the World of Playing Cards is a global collaborative project, with my son Adam serving as the technical driving force behind its development. His innovative efforts have helped shape the site into the thriving hub it is today. You are warmly invited to become a contributor and share your enthusiasm.

Leave a Reply

Your Name

Just nowRelated Articles

Playing Cards: A Secret History

Playing Cards: A Secret History

71: Woodblock and stencil: the hearts

A presentation of the main characteristics of the wood-block courts of the heart suit.

70: Woodblock and stencil : the spade courts

This is a presentation in a more straight forward fashion of the work done by Paul Bostock and me in...

Illustrated Playing Cards, c.1740

Illustrated playing cards featuring comical engravings and rhymes about saints, c.1740.

Fortune Telling playing cards

English Fortune Telling cards probably published c.1770.

Delightful Cards, c.1723

Delightful Cards, containing variety of entertainment for young Ladies and Gentlemen c.1723.

Arms of English Peers

The Arms of English Peers playing cards were first published in 1686. Heraldry, or a knowledge of th...

De la Rue’s 125th anniversary

In around 1955 De la Rue introduced a new coloured joker and a series of aces of spades with a silho...

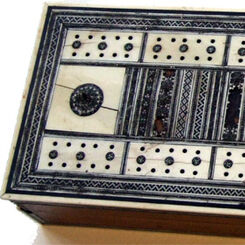

Cribbage Board Collection part 2

A collection of antique and vintage Cribbage Boards by Tony Hall, part 2

Suicide King

The King of Hearts, holding a sword behind his head, is sometimes nicknamed the “Suicide King”. He c...

Pope Joan Trays

Some traditional Pope Joan boards comprise a circular tray, others are square, divided into sections...

19: 19th Century Breaks with Tradition - Unusual versions of the Standard English Pattern

The centuries-long tradition of English court cards was subject to misinterpretation and in some cas...

1: Playing Cards and their History: An Introduction and some links to other sites

What was considered the first mention of playing cards in England is in 1463 when Edward I banned th...

Mathematical Instruments

Mathematical Instruments playing cards forming an instrument maker's trade catalogue, Thomas Tuttell...

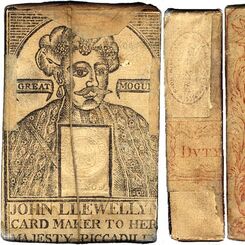

John Llewellyn, playing card manufacturer, London, 1778-1785

John Llewellyn, playing card manufacturer, London, 1778-1785

History of Court Cards

The court cards in English packs of playing cards derive from models produced by Pierre Marechal in ...

Hunt, c.1800

Standard English pattern playing cards manufactured by Hunt, c.1800.

Early English Playing Cards

Early examples of traditional, standard English playing cards of which the best known are those of H...

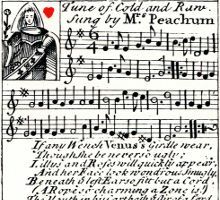

The Beggars’ Opera

The Beggars’ Opera Playing Cards were first published in 1728. The cards carry the words and music o...

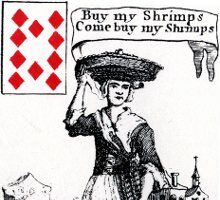

Cries of London

The cards were printed from copper plates, with the red suit symbols being applied later by stencil....

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 60 days

Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here.

Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here. Your comment here.